Math-Functions and Computer Science

19 Mar 2017Over the past few weeks, I’ve been compiling some of the recurring procedures I had used to solve the first 50 problems of Project Euler. While solving these math problems, I needed to find the most efficient method to get the solution. The underlying idea to solve most these are the same and it is pretty simple. But as you proceed, the simple method you had used earlier will take a really long time to produce an answer. So you need to improve upon these methods to make them run faster. Sometimes, you’ll have pushed the simple idea to the extreme and it still won’t work. In that case, you need to come up with a better algorithm or implementation.

In this post, I’ll try to work my way through one of the most commonly used procedure - finding a prime number; checking whether a number is prime; or counting the primes - and how I improved it over the course of solving the first 50 problems. During the discussion, I’ll also attempt to give my most efficient implementation (so far).

Primality test

Perhaps the most simple way to check whether a number is a prime is the trial division taught in elementary school. And it is still very effective. In fact, it is the only method guaranteed to give correct result (a consequence of the definition of prime numbers. It’s true that there are other probabilistic and heuristic tests, but none of them are proved even though they work for numbers larger as 1010 .

isPrime = true;

upper = sqrt(n);

for (int i = 2; i < upper; ++i) {

if (n % i == 0){

isPrime = false;

break;

}

}

return isPrime;This is what I’ve implemented in my library. But, we can clearly do better than this brute force. So I will also bring to light a probabilistic method to solve this. This test was proposed by Fermat. This works for most cases. And in base 2, for numbers up till 2.5∗1010, only 21853 numbers fail. So once can easily store these values in a hash table and if the test passes, searching for this number will reveal whether it is a prime or not.

probablePrime = false;

if (pow(2, n - 1) % n == 1){

probablePrime = true;

}

return probablePrime;Storing primes

Other common problems were finding the nth prime and creating the sieve.

Finding the nth is a very rote approach where I check every number whether it is a prime or not. An improvement to this is to check only the odd numbers. An even better improvement would be to cache all the prime numbers found earlier. Then check the next number only against these prime numbers. This is the final implementation I chose. Another approach would be to use the sieve. But, we need to create a sieve of size larger than position of the nth prime. While there are asymptotic functions that produce such upper bounds, they are not accurate for smaller sizes and this worsens the memory usage.

Now, moving onto the sieve, the problems I came across were relatively of smaller range and a simple Sieve of Eratosthenes served well. However I had to refine it and improve the implementation to hit a decent runtime.

Here is my final implementation of it:

bool* prime = new bool[size + 1];

memset(prime, true, size + 1);

prime[0] = false;

prime[1] = false;

for (int64_t p = 2; p*p <= size; p++) {

if (prime[p] == true) {

for (int64_t i = p * 2; i <= size; i += p) {

prime[i] = false;

}

}

}

return prime;There are a couple of things that I’d like to draw to attention here.

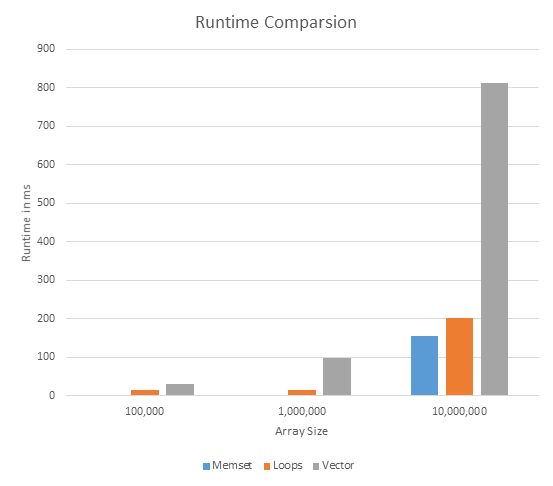

The first thing to notice is that I abandoned the use of vector.

This is plain because, vector is a secondary data structure and they increase the runtime of the program.

With a bool array, the program ran in under a minute.

The second modification I made was abandoning the for loop.

Earlier, I had used a for loop to initialize the values of the array to true.

I did away with this using memset. With memset, the compiler can assign values in any order (fastest order).

However, in a for loop, you are forcing the compiler to go in one direction.

Here is a chart comparing the runtimes. The code can be found here

Thus, I finalized on this procedure, and it works really well so far. The only caveat is that you do need to remember to deallocate any memory to prevent memory leaks.

Final remarks

There are two takeaways from solving these problems:

- Grab a piece of paper and work out the problem by drawing graphs or writing equations. In most cases, you will realize something that you didn’t catch and find that the problem isn’t really that hard. Then, instead of starting by coding a brute force solution, you already have an algorithm to work with. This can save so much time when optimizing brute force.

- Sometimes, writing it out won’t work. You won’t see patterns. Recursion won’t help. In fact, it will only get worse. Then you should quickly implement a dirty brute force. Work your way from there and see how you can optimize it. Skip through loops. Cache items. And if there is an alternative to recursion, almost always choose the alternative because, recursion on large items can cause the stack to overflow (which you don’t want!).